PC Game Piracy Examined

[Page 8] Copy Protection & DRM

Digital Rights Management is a term used to describe any method designed to control the way in which users access digital content. Copy Protection on the other hand is specifically targeted at one particular aspect of digital content rights, namely preventing unauthorized duplication of software. Their application in the gaming industry is basically for much the same purpose: to reduce the number of people creating, distributing or downloading illegal copies of games. Over the years basic copy protection measures have steadily evolved to the point where stronger forms of DRM are being used in the latest games to combat piracy. To consumers, DRM is a four letter word. There are two reasons for this: the potential for legitimate purchasers to experience problems with the various implementations of it; and the perception that DRM, indeed any form of copy protection, is useless against piracy. We examine these issues in more detail in this section.

The Evolution of Copy Protection & DRM

In the early days, games were not covered by any specific copy protection mechanism. This is because various physical and technological limitations made piracy difficult and costly for the average person. For example games for the Atari 2600 console came on special ROM cartridges, and short of buying a device like the Copy Cart, you couldn't pirate the games. Even if you owned such a device "...the cost of the blanks were not much less than prices on regular games." This played a significant part in aiding Atari's sales success: "The 2600 and its cartridges were the main factor behind Atari Inc. grossing more than $2 billion in profits in 1980." Soon most gaming systems would adopt the cartridge because it was an effective anti-piracy device. For this very reason, even as late as 1996 Nintendo opted for a cartridge system for its new 64-bit Nintendo 64 console. However by then, in the face of competition from CD media, this form of protection though highly effective, was no longer ideal:

ROM cartridges are difficult and expensive to duplicate, thus resisting piracy, albeit at the expense of lowered profit margin for Nintendo. While unauthorized interface devices for the PC were later developed, these devices are rare when compared to a regular CD drive and popular mod chips as used on the PlayStation. Compared to the N64, piracy was rampant on the PlayStation.

While the early gaming consoles had an effective method of combating piracy, the PC and hybrid gaming computers such as the Amiga 500 and the Commodore 64 were not so lucky because the floppy disk and tape media they used were relatively cheap and hence increasingly more attractive to pirates. For this reason, the majority of games for these systems started implementing some form of protection. Methods included hidden low-level code or non-standard physical attributes in the media to make them harder to copy, or even the presence of a special 'dongle' that needed to be plugged into the back of the machine to prevent illegal copies working. Often games would require the entering of specific words from the manual before the user was allowed to proceed further. Some copy protection methods went even further, as this article on the 1993 DOS game Call of Cthulhu describes:

The original Floppy Disk version (1993) came with a bizarre copy protection method, the 'Arkham Planetarium Invitation'. The card folded out into a box which contained a magnifying glass on one side, and inside was a star chart written as a grid. When the game was started various constellations were shown. Then, using the star chart you had to look through the magnifying glass and find the corresponding constellation, noting its coordinates on the grid.

Back in 1988, as a teenager I worked in a local computer store selling Amiga 500s as a summer job and I can recall all the various protection methods which popular Amiga games used. In our youthful foolishness, my co-workers and I tried many times to copy a popular new game called Faery Tale Adventure - think of it as the '80s version of Elder Scrolls Oblivion. We tried various well-known cracking tools but never fully succeeded; in every copy the early loading screens and the game's music came out badly garbled and the game crashed randomly. We weren't alone, because to this day even if you find a professionally cracked copy of Faery Tale Adventure (e.g. for use with an Amiga Emulator), it will display similar problems. In addition to this stubborn protection method, the game also had an initial quiz screen which required the input of several random words from the manual, meaning home-made copies had to be accompanied by a copy of the manual, which back then meant having access to a photocopying machine.

So the copy protection scheme on Faery Tale Adventure presented a non-intrusive but solid defense against not only bored computer store workers, but anyone who bought the game and then wanted to make copies for friends and neighbors. Yes the game was cracked and glitchy pirated versions eventually distributed around the world, but back then in the absence of the Internet the only way for the average person to get pirated games was to swap with their friends. If your buddies didn't have the game then the only alternatives were to wait a while or buy the game. To end my anecdote, I couldn't wait and wound up buying a copy of Faery Tale Adventure a few days later as I really wanted to play it.

It was the explosion in the take-up of the consumer Internet that was to revolutionize piracy, and present an entirely new challenge for protecting content against unauthorized duplication. Just as the invention of the mechanical printing press in 1439 opened the doors to unauthorized duplication of books on a scale never imagined before, the Internet allowed the average home user to instantly share pirated software with a virtual community of millions as opposed to a handful of close friends. At first when PC games moved to the CD ROM format in the 1990s, the large size and relatively high cost of duplicating CDs afforded some temporary protection against rampant piracy. Distributing 700MB CD copies over the Internet wasn't really viable at average download speeds of ~5 KB/s, so the pirated games which were being distributed were called 'rips' - large portions of the games such as cut-scene movies, music, sound effects and other miscellaneous files were excluded to reduce the download size. Aside from the fact that many people still didn't have Internet access at home back then, there was also no central distribution channel, making these rips harder to find for the average person, and of course the lower quality and lengthy download times made them far less desirable.

Then along came first Napster in 1999, then Kazaa in 2001, and eventually Bittorrent in the latter part of 2002, providing increasingly easier ways for less tech-savvy people to find and download all sorts of pirated material using a simple Graphical User Interface. The final phase of the piracy revolution came with rapidly rising broadband adoption. Piracy groups quickly abandoned rips for perfect quality 1:1 .ISO copies of games. The declining cost of CD burners and blank CDs, as well as larger and cheaper hard drives meant that in the early 21st century piracy was soon a cheap and easy exercise for the average person to conduct. This heralded an entirely new chapter in the arms race between content owners and pirates.

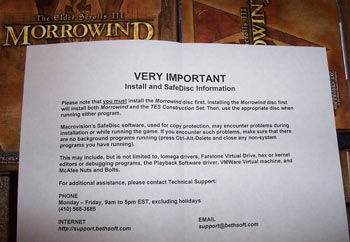

The content owners' response to these new challenges came in the form of various copy protection methods developed by a range of companies such as Macrovision and Sony. Many of these protection methods were ineffective or problematic. They ranged from basic disc checks to the progressively more complex low-level methods of successive generations of the SafeDisc, StarForce, SecuROM and Tages protection systems. As a consequence, while these protection/DRM methods have had varying degrees of success over the years, they've also introduced a range of potential problems for legitimate purchasers of games as well. One common misconception is that protection systems in the past were not as potentially problematic as more recent methods, which is false. My copy of Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind from 2002 comes with a separate slip of paper that carries a clear warning from the developers regarding SafeDisc:

In recent times however the controversy over the use of copy protection and DRM has reached almost hysterical proportions and no longer bears much resemblance to the actual facts.

Copy Protection & DRM Don't Work

Many people will blurt out what they believe is the ultimate argument against copy protection and DRM: "It doesn't work!". This claim is borne out of the misconception that the games industry is using copy protection or DRM measures to completely eliminate piracy, which is absurd. It's common knowledge both within the gaming industry and outside it that piracy cannot be stopped completely. If properly motivated, and given enough time, pirates can and will break through virtually any software or hardware-based defence mechanism. The rationale behind the use of copy protection and DRM is much the same as the rationale behind the use of physical locks: to increase the complexity, time, effort and risk involved in attempting to overcome the protection, in the hopes of discouraging 'casual' pirates and thieves. In other words whether a physical lock or a digital lock, the aim is essentially to keep honest people honest, not to present an impenetrable barrier.

Consider this: nothing can prevent a thief from breaking into your house if they really want to. Those locks and security systems which homeowners install throughout their property can't stop someone from breaking a window to gain entry for example, or picking the locks, or in extreme cases, simply driving a stolen car through the front of the house. In fact it doesn't even require a 'hardcore' thief to overcome a property's protection. Through the simple technique of Lock Bumping, virtually any lock can be picked within 5 minutes and without a trace. In the spirit of DRM hysteria, here's a more sensationalist take on the issue: Nearly Every Lock You Have Is Now Worthless. Even if you upgrade your locks to try to overcome this vulnerability, consider the new SneaKey technique which allows potential thieves to create perfect duplicates of keys using only some software and a standard resolution digital photograph of the key - even from a picture taken at a distance of up to 200 feet away.

So really, all locks and keys do 99% of the time is present a constant inconvenience for legitimate users. If we lose them, we're locked out of our own houses or cars. Yet strangely enough, you won't find a groundswell of popular opinion stating firmly around the Internet that "door locks don't work!" and demanding that everyone remove them because of the inherent inconvenience that they impose. Why is that? Probably because everyone is the owner of physical property of some kind, and is willing to endure the constant inconvenience of various locks and keys in their daily lives in the hopes of protecting that property from potential theft, even if in reality it actually provides them with no real protection against most thieves. However because most people are not owners of intellectual property, they find it exceedingly easy to flippantly shout simplistic solutions across the Internet such as "Greedy companies must remove all protection and DRM, they don't work!".

Again, the aim of these protection methods is to increase the cost barrier and risks of casual piracy. A lock on your door may be picked within 5 minutes by someone using the right tools, but for the average person who comes up to the front door of your house and tries to open it, the lock presents an adequate barrier against casual theft. Similarly copy protection won't stop someone familiar with cracking tools, nor someone who knows how to use torrents, but it can prevent casual gamers who've bought a copy from sharing it with all their friends for example.

In actual point of fact there are many recent examples where copy protection and DRM has worked extremely well in reducing not only casual piracy, but also preventing hardcore piracy.

In online gaming for example, the use of serial numbers for verification of ownership has been very successful in reducing the incentive to pirate them. This is one of the secrets behind World of Warcraft's success which has 11 million subscribers, and also the reason for the sales success of predominantly online games such as EA's Battlefield series which has sold 17 million copies. Online verification also factors immensely into the success of Valve's Steam distribution model, which we discuss later. It's important to note that serial number protection methods are easily cracked, and people have set up unofficial servers on which pirated copies of these online games are being played, however because most players are on the official servers which the pirates can't join, the incentives for piracy are greatly reduced.

For offline games, the problem of protection is much more complex. As expected all offline protection systems have eventually been cracked, and once cracked, a pirated version of an offline game is identical to the legitimate version in terms of gameplay experience. However the SecuROM, StarForce and Tages protection methods in particular have presented a strong barrier against being cracked, and the end result has been that proper working pirated versions of some games have not been available prior to the game's official release, and sometimes not even a week or two afterwards. This delay and the resulting uncertainty in the availability of a pirated copy, however brief, can drive some impatient gamers to actually purchase the game rather than wait for a working crack to appear. There are several examples of copy protection/DRM being quite effective at preventing piracy for a period of time:

Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory, released on 28 March 2005, utilizes the StarForce protection method. As unpopular as this protection method was, it worked to protect the game from any piracy for over a year (422 days) before a working crack was released. No doubt at least some of the people who had wanted to illegally download the game couldn't wait an entire year for the crack to show up, and eventually bought the game regardless. Of course this level of protection came at a cost in terms of negative publicity, and some known compatibility issues. However as we'll see shortly, the fear campaign against StarForce was fuelled by deliberate and unproven misinformation.

BioShock was released on 21 August 2007, sporting a new version of SecuROM protection incorporating an online activation method. It wasn't until almost two weeks later that a working crack for the game was released, and in fact the crack came from an unknown third party, because the established cracking groups had been unsuccessful in getting around this version of SecuROM. 2K Games' Martin Slater said in this interview:

We achieved our goals. We were uncracked for 13 whole days. We were happy with it. But we just got slammed. Everybody hated us for it. It was unbelievable... There is a lot of strain on our content-delivery servers and things like that, where everyone has to download a 10MB executable. I don't think we'll do exactly the same thing again, but we'll do something close. You can't afford to be cracked. As soon as you're gone, you're gone, and your sales drop astronomically if you've got a day-one crack.

More recently, the online activation methods of Mass Effect and GTA IV have similarly prevented fully working pirated versions of these games from being available until at least several days after their official release, and definitely not before release. What most users don't consider is that 'day-one' or 'day-zero' piracy as it's called is disproportionately more damaging to a game's sales than at any other time, as this article explains:

Day zero piracy is where a game is released for free by pirates before the official release. It's disastrous for the developer and publisher because whatever route gets the game out to the gamer first will be the favoured choice, so a game uploaded to the internet before the release date will have a huge impact on sales.

It's around the release period when marketing hype has reached fever pitch, and gamers are most excited about getting a game. If a working pirated version is available at the same time, the potential for lost sales is enormous. Pete Hines of Bethesda Softworks recently confirmed the same thing when discussing concerns about Fallout 3's release, saying in response to a question about day-one piracy: "Yeah, it's a huge problem. Huge."

This initial sales rush has a lot to do with intense competition in the industry, particularly towards the holiday season when the relatively short attention span of gamers is challenged by one big release after another, each title only having a brief moment in the spotlight before it's superseded by the 'next big game'. As this article notes, the issue is particularly relevant to big-name titles which hardcore gamers enjoy, rather than the more casual games:

With so many AAA games coming out at such regular intervals, there's not as much time for people to discover or savor older games. The only exception, ironically, are more casually oriented games that rarely have big initial sales pops.

In any case the big marketing hype and hence the big sales occur within a short space of time around the games release date, and that's also the time when a game can be sold for full retail price; the older the game becomes, the less people are interested in it and the lower its price needs to fall to remain attractive. So to protect games, copy protection or DRM doesn't need to be impervious to piracy, it simply needs to hinder casual piracy and day-zero piracy, and also not only make the process more of a hassle for would-be pirates, but place uncertainty in their minds as to how long it will actually take to get their hands on a working bug-free crack for the game. While 'hardcore' pirates will always wait for a crack, even a few days' delay can affect a person who may have been sitting on the fence between pirating a game or purchasing it, especially if a legitimate digital copy is only a download away from somewhere like Steam. A quick look at the comments on some piracy sites for the torrents of games which have more robust DRM will show you that this approach appears to work in netting extra sales. Comments like this one for a non-working GTA IV crack are becoming relatively common: "doesnt work for me …however i will now buy it over steam …the devs earned some bucks".

Even the makers of StarForce DRM have said exactly the same thing regarding the use of their protection technology. On the StarForce forums they said this:

The purpose of copy protection is not making the game uncrackable - it is impossible. The main purpose is to delay the release of the cracked version. Maximum sales rate usually takes place in the first month(s) after the game release. If the game is not cracked in that period of time, then the copy protection works well.

In short, copy protection and DRM often do work to achieve what they specifically set out to do - to prevent casual piracy and protect games against piracy in the initial sales period. Shortly I discuss an even more concrete example of one particular form of DRM which is wildly successful: Steam.

DRM Causes Piracy

Some people argue that because various copy protection and DRM methods can cause potential problems for legitimate purchasers, this in effect drives a proportion of legitimate purchasers to piracy in an effort to rid themselves of these problems. This is logically plausible, in that based on various comments around the Internet, it appears that some people genuinely believe that the only way they can avoid the supposedly horrendous impacts of DRM is to pirate a game rather than purchase it.

However firstly we need to consider how we got into this situation in the first place. Newton's Third Law of Motion states: "To every action there is an equal and opposite reaction." Games didn't originally come with any intrusive protection. Over time, as we've seen from the data in earlier sections of this article, piracy has come to reach truly staggering proportions, and imposes various costs and risks on developers and publishers. Faced with the extreme situation of potentially more people pirating a game than there are legitimate purchasers, and thus the vast majority of their 'customers' being people who are free riders that contribute absolutely nothing, indeed many of them even drawing on expensive tech support resources for games which they've pirated, games companies have resorted to DRM as an equally extreme response.

The argument that removing DRM will result in a net increase in sales has no basis in fact based on the evidence at hand. Not only does gaming history show that unprotected games simply lead to more piracy, recent history also demonstrates clearly that simply removing DRM is not the answer to piracy. As we saw in the Scale of Piracy section, many popular games which have no intrusive DRM, such as Assassin's Creed, Crysis, Call of Duty 4 and World of Goo, also have some of the highest piracy rates in 2008. Indeed as I write this, the new Prince of Persia game was released yesterday for PC (December 10, 2008) with absolutely no DRM protection, and a quick look at torrents shows that the pirated version is available, and on two popular torrent links alone there are over 23,000 people downloading the game within the first 24 hours. The evidence is overwhelmingly clear: DRM does not cause piracy, piracy results in DRM.

Update: As yet another example of removing DRM not leading to any reduction in piracy, the game Demigod has been pirated so heavily in its initial release period that it has caused the game's servers to effectively go down. Out of the 120,000 connections made to the game's servers, over 100,000 were by confirmed pirates, leaving only around 18,000 legitimate purchasers. The game is released by Stardock, a relatively small company which has a lot of public support due to the mistaken perception that Brad Wardell, CEO of Stardock is anti-DRM (see the bottom of the next page for more details of Stardock's actual position). Demigod is widely considered to be a good game, it's available as a digital download priced at under $40, and has no intrusive DRM - yet not only has this not stopped the game from being rampantly pirated, preventing legitimate purchasers from playing the game, but has also resulted in poor reviews, potentially affecting future sales of the game.

Another excellent example of piracy forcing copy protection measures and not the other way around comes from a recent development in the field of Linux gaming. By way of background, Linux users, as open-source advocates, are notorious for presenting themselves as enlightened champions of fair play, always insisting that they'll reward any company that doesn't use protected software. For many years Linux Game Publishing (LGP) had been releasing Linux-ported versions of popular games with no copy protection or DRM. In mid-2008 this all changed as LGP was forced to take steps to incorporate a copy protection system for their games. Michael Simms the CEO of Linux Game Publishing explains the rationale for this reluctant decision:

Trust me, I don't like it, I'm not happy about it, but we HAVE to do this. I've fought for 6 years against the need for any kind of protection system and all that's happened is that for every legitimate copy of an LGP game out there, there are probably 3-4 pirated copies. That's the difference between success and failure. ...we have to face reality in that many many people buy games and put them online for people to download. Hell, we even get people asking for tech support on games we KNOW are pirated... I agree, if some people wouldn't buy anyway, then this wont persuade them to, but you know what, I place a value on the work LGP does, and if the people want to take our work for nothing, I have no problem in denying them from doing that. I can't afford, and nor can my [development team], to have it continue. I can say, we aren't doing this to pillage the last few pounds we can from a game, I'm saying this is being done to try and ensure we can make games into the future.

Clearly they are willing to risk losing a few DRM-hating customers if it means dumping the free riders and making the difference between staying viable and going out of business.

A recent highly-publicized PC-specific example of the 'DRM causes piracy' argument is the game Spore, and in some ways this is a unique case that bears closer examination. Much-maligned for its use of SecuROM DRM, some people even went to the trouble of giving Spore a one-star rating on Amazon.com to protest the use of DRM. Similarly, looking at Spore's Metacritic Scores, it got 84% from professional reviewers, but a lowly 45% from users, primarily due to the DRM issue. Despite this customer backlash, the game still sold over 2 million copies in its first three weeks alone, making it one of the best selling PC games of the year. To counter this success, one piracy site released the sensationalist claim that Spore is the most downloaded game ever at 500,000 copies during the same period. I have no doubt that some of those pirated copies were the result of people being scared off by SecuROM, however the entire Spore controversy is more important because it demonstrates the somewhat sinister side of the DRM debate. As I'm about to show you, the anger against SecuROM - and StarForce before it - is in large part propagandistic misinformation-laden scaremongering deliberately fuelled by various vested interests. For the moment, to counter the Spore example, bear in mind that the piracy figures we examined earlier show that the key determinant in how much a game gets pirated is how popular the game is, not whether it has DRM.

DRM is Malware

The fact of the matter is that whether successful in preventing a net loss in sales or not, nobody likes copy protection and DRM - not legitimate purchasers who may experience problems with it, not the pirates who have to work to crack it, and not the developers and publishers who have to pay substantial sums to the companies that own the technology, not to mention having to face the constant negative publicity and tech support requests. EA boss John Riccitiello recently said this about the Spore controversy:

I personally don't like DRM. It interrupts the user experience. We would like to get around that. But there is this problem called piracy out there. We're still working out the kinks. We implemented a form of DRM and it's something that 99.8 percent of users wouldn't notice. But for the other .2 percent, it became an issue and a number of them launched a cabal online to protest against it.

Note that he got the '0.2%' figure from the data provided here which shows that from a large sample of Spore customers, less than 1% of customers ever faced the DRM-enforced installation limit. Regardless of whether it was only 1% or not, ideally no legitimate customer should have to face potentially troublesome installation limits, forced to make phone calls to EA Support to explain activation issues, and generally spend their time dealing with potential problems rather than playing their game. However there's a world of difference between not liking something that's an inconvenience but a practical necessity, and hysterically hating it based on hearsay and misinformation. Many users have problems with their graphics drivers for example, spending hours reinstalling, configuring and troubleshooting them in an effort to play their games with stability and decent performance - but that doesn't mean everyone should start a hate campaign filled with unsubstantiated falsehoods against ATI or Nvidia.

There are two specific protection systems which have been targeted for heavy doses of user hatred: StarForce and SecuROM. It's time to put an end to the hearsay and uninformed nonsense once and for all, and examine the facts regarding these protection systems.

On the next page we take a closer look at StarForce and SecuROM, as well as Steam.